What HTTP/2 Means for Ruby Developers

Okay, way too much magical pixie dust

HTTP/2 is coming! No, wait, HTTP/2 is here! After publication in Q1 of 2015, HTTP/2 is now an “official thing” in Web-land. As of writing (December 2015), caniuse.com estimates about 70% of browsers globally can now support HTTP/2. So, I can use HTTP/2 in my Ruby application today, right? After all, Google says that some pages can load up to 50% faster just by adding HTTP/2/SPDY support, it’s magical web-speed pixie dust! Let’s get it going!

Uh, hello Aaron? Yeah, could you like, fix Rack

please?

Well, no. Not really. Ilya Grigorik has written an experimental HTTP/2 webserver in Ruby, but it’s not compatible with Rack, and therefore not compatible with any Ruby web framework. While @tenderlove has done some experiments with HTTP/2, Rack remains firmly stuck in an HTTP/1.1 world. While it was discussed that this would change with Rack 2 and Rails 5, very little actually changed. Until the situation changes at the Rack level, Rails and all other Ruby web frameworks are stuck with HTTP/1.1.

Part of the reason why progress has been slow here (other than, apparently, that @tenderlove is the only one that wants to work on this stuff) is that Rack is thoroughly designed for an HTTP/1.1 world. In a lot of ways, HTTP/2’s architecture will probably mean that whatever solution we come up with will bear more resemblance to ActionCable than it does to to Rack 1.0.

Ilya Grigorik, Google’s public web performance advocate, has laid out 4 principles for the web architecture of the future. Unfortunately, Rack is incompatible with most of these principles:

- Request and Response streaming should be the default. While it isn’t the default, Rack at least supports streaming responses (it has for a while, at least).

- Connections to backend servers should be persistent. I don’t see anything in Rack that stops us from doing this at the moment.

- Communication with backend servers should be message-oriented. Here’s one of the main hangups - Rack is designed around the request/response cycle. Client makes a request, server makes a response. While we have some limited functionality for server pushes (see ActionController::Live::SSE), communication in Rack is mostly designed around request/response, not arbitrary messages that can go in either direction.

- Communication between clients and backends should be bi-directional. Another problem for Rack - it isn’t really designed for pushes straight from the server without a corresponding request. Rack essentially assumes it has direct read/write access to a socket, but HTTP/2 complicates that considerably.

If you’re paying attention, you’ll realize these 4 principles sound a hell of a lot like WebSockets. HTTP/2, in a lot of ways, obviates Ruby developers’ needs for WebSockets. As I mentioned in my guide to ActionCable, WebSockets are a layer below HTTP, and one of the major barriers of WebSocket adoption for application developers will be that many of the things you’re used to with HTTP (RESTful architecture, HTTP caching, redirection, etc) need to be re-implemented with WebSockets. Once HTTP/2 gets a JavaScript API for opening bi-directional streams to our Rails servers, the reasons for using WebSockets at all pretty much evaporate.

When these hurdles are surmounted, HTTP/2 could bring, potentially, great performance benefits to Ruby web applications.

HTTP/2 Changes That Benefit Rubyists #

Here’s a couple of things that will benefit almost every web application.

Header Compression #

One of the major drawbacks of HTTP 1.1 is that headers cannot be compressed. Recall that a traditional HTTP request might look like this:

accept:text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

accept-encoding:gzip, deflate, sdch

accept-language:en-US,en;q=0.8

cache-control:max-age=0

cookie:_ga=(tons of Base 64 encoded data)

upgrade-insecure-requests:1

user-agent:Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/47.0.2526.73 Safari/537.36

Cookies, especially, can balloon the size of HTTP requests and

responses. Unfortunately, there is no provision in the HTTP

1.x specification for compressing these - unlike response

bodies, which we can compress with things like

gzip.

Huffman coding, duh!

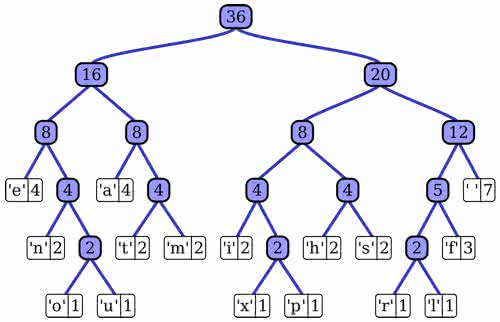

Headers can make up 800-1400KB of a request or response - multiply this to Web Scale and you’re talking about a lot of bandwidth. HTTP/2 will reduce this greatly by compressing headers with something fancy called Huffman coding. You don’t really need to understand how that works, just know this - HTTP/2 makes HTTP headers smaller by nearly 80%. And you, as an application author, won’t need to do anything to take advantage of this benefit, because the compression/decompression will happen at lower levels (probably in Rack or some new layer directly below).

This compression will probably be one of the first HTTP2 features that Rails apps will be able to take advantage of, since header compression/decompression can happen at the load balancer or at the web server, before the request gets to Rack. You can take advantage of header compression today, for example, by placing your app behind Cloudflare’s network, which provides HTTP/2 termination at their load balancers.

Multiplexing #

Damn, shoulda multiplexed.

Multiplexing is a fancy word for two-way communication. HTTP 1.x was a one-way street - you could only communicate in one direction at a time. This is sort of like a walkie-talkie - if one person is transmitting with a walkie-talkie, the person on the other walkie-talkie can’t transmit until the first person lets off the “transmit” button.

On the server side, this means that we can send multiple responses to our client over a single connection at the same time. This is nice, because setting up a new connection is actually sort of expensive - it can take 100-500ms to resolve DNS, open a new TCP connection, and perhaps negotiate SSL.

Multiplexing will completely eliminate the need for domain sharding, a difficult-to-use HTTP 1.x optimization tactic where you spread requests across multiple domains to get around the browser’s 6-connections-per-domain limit. Instead of each request we want to make in parallel needing a new connection, a client browser can request several resources across the same connection.

I mentioned domain sharding was fraught with peril - that’s because it can cause network congestion. The entire reason the 6-connections-per-domain limit even exists is to limit how much data the server can spit back at the client at one time. By using domain sharding, we run the risk of too much data being streamed back to clients and causing packet loss, ultimately slowing down page loads. Here’s an awesome deconstruction of how domain sharding too much actually slowed down Etsy’s page loads by 1.5 seconds.

One area where Rails apps can take advantage of multiplexing today is by using an HTTP/2 compatible CDN for serving their assets.

Stream Prioritization #

HTTP/2 allows clients to express preferences as to which requests should be fulfilled first. For example, browsers can optimize by asking for JS and CSS before images. They can sort of do this today by delaying requests for resources they don’t want right away, but that’s pretty jank and fraught with peril.

As an example, here’s an article about how stream prioritization sped up a site’s initial paint times by almost 50%.

Again, your Ruby app can take advantage of this right now by using an HTTP/2 compatible CDN.

Latency Reduction #

HTTP/2 will especially benefit users in high-latency environments like mobile networks or developing countries. Twitter found that SPDY (the predecessor to HTTP/2) sped up requests in high-latency environments much more than in low-latency ones.

Binary #

HTTP/2 is a binary protocol. This means that, instead of plain text being sent across the wire, we’re sending 1s and 0s. In short, this means HTTP/2 will be easier for implementers, because plain-text protocols are often more difficult to control for edge-cases. But for clients and servers, we should see slightly better bandwidth utilization.

Unfortunately, this means you won’t be able to just

telnet

into an HTTP server anymore. To debug HTTP/2 connections,

you’re going to need to use a tool that will decode it for

you, such as the browser’s developer tools or something like

WireShark.

One connection means one TLS handshake #

One connection means TLS handshakes only need to happen once per domain, not once per connection (say, up to 6 TLS handshakes for the same domain if you want to download 6 resources from it in parallel).

Rails applications can experience the full benefit of this HTTP/2 feature today by being behind an HTTP/2 compatible web server or load balancer.

How Rails Apps Will Change with HTTP/2 #

All of the changes I’ve mentioned so far will generally benefit all Ruby web applications - but if you’ll permit me for a minute, let’s dive in to Rails as a specific example of your applications may have to change in the future to take full advantage of HTTP/2.

Primarily, HTTP/2 will almost completely upend the way Rails developers think about assets.

Concatenation is no more #

In essence, all HTTP/2 does is make requests and responses cheaper. If requests and responses are cheap, however, suddenly the advantages of asset concatenation become less clear. HTTP/2 can transport a JS file in 10 parts pretty much as fast as it can transport that same file in 1 part - definitely not the case in HTTP/1.x.

In HTTP/1.x-world, we’ve done a lot of things to get around the fact that opening a new connection to download a sub-resource was expensive. Rails concatenated all of our Javascript and CSS into a single file. Some of us used frameworks like Compass to automatically sprite our images, turning many small .pngs into one.

But since HTTP/2 makes many-files just as cheap as one-file, that opens up a whole new world of advantages for Rails:

- Development mode will get waaaay faster. In development mode, we don’t concatenate resources, meaning a single page often requires dozens of scripts and css files. HTTP/2 should make this just as fast as a single concatenated file in production.

- We can experiment with more granular HTTP caching schemes. For example, in todays Rails’ world, if you change a single line in your (probably massive) application.js, the entire file will need to be re-downloaded by all of your clients. With HTTP/2, we’ll be able to experiment with breaking our one-JS and one-CSS approach into several different files. Perhaps you’ll split out high-churn files so that low-churn CSS won’t be affected.

- We can amortize large amounts of CSS and JS over several page loads. In today’s Rails world, you have to download all of the CSS and JS for the entire application on the first page load. With HTTP/2 and it’s cheap connections, we can experiment with breaking up JS and CSS on a more granular basis. One way to do it might be per-controller - you could have a single base.css file and then additional css files for each controller in the app. Browsers could download bits and pieces of your JS and CSS as they go along - this would effectively reduce homepage (or, I guess, first-page) load times while not imposing any additional costs when pages included several CSS files.

Server push really makes things interesting #

HTTP/2 introduces a really cool feature - server push. All this means is that servers can proactively push resources to a client that the client hasn’t specifically requested. In HTTP/1.x-land, we couldn’t do this - each response from the server had to be tied to a request.

Consider the following scenario:

-

Client asks for

index.htmlfrom your Rails app. -

Your Rails server generates and responds with

index.html. -

Client starts parsing

index.html, realizes it needsapplication.cssand asks your server for it. -

Your Rails server responds with

application.css.

With server push, that might look more like this:

-

Client asks for

index.htmlfrom your Rails app. -

Your Rails server generates and responds with

index.html. While it’s doing this, it realizes thatindex.htmlalso needsapplication.css, and starts sending that down to the client as well. - Client can display your page without requesting any additional resources, because it already has them!

Super neato, huh? This will especially help in high-latency situations where network roundtrips take a long time.

Interestingly, I think some of this means we might need to serve different versions of pages, or at least change Rails’ server behavior, based on whether or not the connection is HTTP/2 or not. Hopefully this will be automatically done by the framework, but who knows - nothing has been worked on here yet.

How to Take Advantage of HTTP/2 Today #

If you’re curious about where we have to go next with Rack and what future interfaces might look like in Rails for taking advantage of HTTP/2, I find that this Github thread is extremely illuminating.

For all the doom-and-gloom I just gave you about HTTP/2 still looking a ways off for Ruby web frameworks, take heart! There are ways to take advantage of HTTP/2 today before anything changes in Rack and Rails.

Move your assets to a HTTP/2 enabled CDN #

An easy one for most Rails apps is to use a CDN that has HTTP/2 support. Cloudflare is probably the largest and most well-known.

There’s no need to add a subdomain - simply directing traffic through Cloudflare should allow browsers to upgrade connections to HTTP/2 where available. The page you’re reading right now is using Cloudflare to serve you with HTTP/2! Open up your developer tools to see what this looks like.

Use an HTTP/2 enabled proxy, like nginx or h20. #

You should receive most of the benefits of HTTP/2 just by proxying your Rails application through an HTTP/2-capable server, such as nginx.

For example, Phusion Passenger can be deployed as an nginx module. nginx, as of 1.9.5, supports HTTP/2. Simply configure nginx for HTTP/2 as you would normally, and you should be able to see some of the benefits (such as header compression).

With this setup, however, you still won’t be able to take advantage of server push (as that has to be done by your application) or the websocket-like benefits of multiplexing.

Want a faster website?

I'm Nate Berkopec (@nateberkopec). I write online about web performance from a full-stack developer's perspective. I primarily write about frontend performance and Ruby backends. If you liked this article and want to hear about the next one, click below. I don't spam - you'll receive about 1 email per week. It's all low-key, straight from me.

Products from Speedshop

The Complete Guide to Rails Performance is a full-stack performance book that gives you the tools to make Ruby on Rails applications faster, more scalable, and simpler to maintain.

Learn more

The Rails Performance Workshop is the big brother to my book. Learn step-by-step how to make your Rails app as fast as possible through a comprehensive video and hands-on workshop. Available for individuals, groups and large teams.

Learn more

More Posts

Announcing the Rails Performance Apocrypha

I've written a new book, compiled from 4 years of my email newsletter.

We Made Puma Faster With Sleep Sort

Puma 5 is a huge major release for the project. It brings several new experimental performance features, along with tons of bugfixes and features. Let's talk about some of the most important ones.

The Practical Effects of the GVL on Scaling in Ruby

MRI Ruby's Global VM Lock: frequently mislabeled, misunderstood and maligned. Does the GVL mean that Ruby has no concurrency story or CaN'T sCaLe? To understand completely, we have to dig through Ruby's Virtual Machine, queueing theory and Amdahl's Law. Sounds simple, right?

The World Follows Power Laws: Why Premature Optimization is Bad

Programmers vaguely realize that 'premature optimization is bad'. But what is premature optimization? I'll argue that any optimization that does not come from observed measurement, usually in production, is premature, and that this fact stems from natural facts about our world. By applying an empirical mindset to performance, we can...